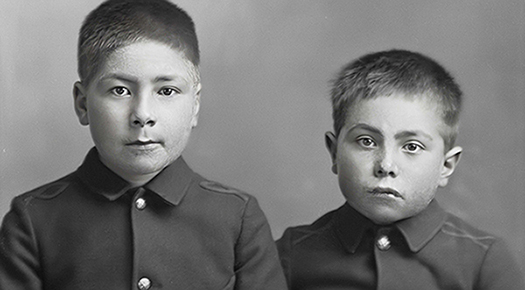

For generations, going to school for some Native Americans not only meant doing what they were told but using English names and being unable to speak in their native tongue. Some students were even met with beatings, withholding of food and solitary confinement.

Forest Grove residents will get a better understanding of the Native American boarding school experience at an advanced screening of a documentary at 6 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 28, at Pacific University's Taylor Meade Auditorium in Forest Grove.

The 60-minute Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) documentary follows Klamath Tribes member Gabriann “Abby” Hall as she discovers her family’s experiences in Native American boarding schools.

Three generations of her relatives were among tens of thousands of Indigenous children removed from their homes by the federal government and placed in boarding schools. This was part of U.S. policy from 1819 until the 1970s “to assimilate tribes into mainstream society,” according to the adapted short version of “Uncovering Boarding Schools: Stories of Resistance and Resilience.”

The documentary — due to premiere on OPB-TV and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) website and app on Nov. 3 at 9 p.m. — was made by Native American crew members and narrated by Umatilla tribal member Acosia Red Elk, known for her world-champion jingle dancing.

How it started

Hall knew that her grandmother, Marilyn Mae Mitchell, ended up in boarding schools along with her two sisters. “I knew that she didn’t really talk about it,” Hall said about her grandmother.

Funded by an Oregon Department of Education grant to the Klamath Tribe, Hall began digging through records to uncover her family’s story. She found “the history had not been written,” she told Ashland.news in a Zoom call. “It’s undeniable that the government has tried to cover this up. You don’t read about it in history books. It’s void of information.”

After finding zero documentation of what she was looking for, Hall reached out to OPB producer Kami Horton in 2021 for her experience in historical documentaries. This commenced a two-year long research endeavor.

Through interviews with over 20 elders and help from other researchers, Horton and Hall tracked down family members’ documents and searched through archives across the country. They discovered an untold history of countless deaths and unjust treatment as well as a legacy of resistance and resilience.

They learned Hall’s grandmother and many other children from her family attended religious facilities that do not appear as “official” Native American boarding schools — uncovering six religious institutions in Oregon paid for by the federal government.

On the same call, Horton said, “Abby’s grandmother’s story really opens things up. That was the initial point of discovering there were not just these federally operated boarding schools that we know some about, but there were also all of these religious schools that are not listed.”

Hall found out her grandmother was separated from her two sisters at Steward Indian School in Nevada and sent to Haskell Indian School in Kansas. She also learned her grandmother went to Canyonville Bible Academy in Douglas County, Oregon, beforehand.

“One of my greatest regrets is not talking to my grandma more,” Hall said, “but even if I had initiated those conversations, would she have been in a space and a place to talk about it?”

She encourages others to “ask your elders before it’s too late,” even though it might not be an easy conversation.

The history of boarding schools

The first off-reservation boarding school opened in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1879, the short video explained. More than 10,000 Native American children from over 140 tribal nations attended school there.

Hall’s distant cousin, Mabel Hood, attended Carlisle Indian School. She got sick and was put on a train across the United States with no notice to her family that she’s coming home. Horton uncovered an article about “this little Indian girl that wouldn’t talk, wouldn’t eat and was deserted at the train depot with tuberculosis,” Hall said.

She explained, schools would send sick children home in case they died on the campus despite knowing they were highly contagious. Their tribes would take care of them, Hall said, and then the illness would spread.

In 1880, the federal government opened the second off-reservation boarding school in Forest Grove which would eventually become the Chemawa Indian School in Salem — still open today. The documentary says at least 270 children died while at Chemawa, often from tuberculosis.

Eventually, there would be hundreds of Native American boarding schools across the country, many run by churches.

“Suddenly you could make no decisions,” Klamath tribes elder Clayton Dumont, Sr. said in the short-form documentary. He continued to explain the abuse his 3rd and 4th grade teacher, Sister Veronica inflicted by pulling hair or hitting with the metal part of a ruler.

No time to waste

Hall explained the importance of uncovering this history for her and her tribe: “It was a story that hadn’t been told, and we were coming out of a pandemic where a lot of elders passed away.” The third reason Hall added was they had elders willing to open up after all this time not talking about their experience.

Hall said, “We were losing the history with every elder that passed. Every day it seemed like we were losing the knowledge in the oral story.”

Right before an interview with an elder who attended St. Mary’s boarding school, the elder started not to feel good and went home before he shared his story. “That elder passed within a couple months,” Hall said to Ashland.news “Nobody had really gotten his history formally recorded. It put it at the forefront of not delaying. The timing is now.”

Stories of resistance and resilience

Hall said the strength, resilience and resistance of Native American ancestors is like “DNA” that runs through generations. “If you’re having a bad day at school,” she said. “What’s that compared to what your grandma’s day at school was in a boarding school?”

Horton explained they wanted to highlight the strength and resilience despite the federal government’s attempt to “kill” Native American culture, language and history. She noted the case of the girls at the Klamath Agency Boarding School who burned down the girls dormitory, which ultimately led to the closing of the school.

“You see this pride being re-instilled in our community,” Hall said, referring to youth tribal council speaking in Klamath and seeing more braids in school. “The boarding schools did the exact opposite. They knocked it out. They were beaten for speaking that language. Now the younger generation knows it with greater fluency than us older people do.”

Marking a “full circle,” she continued, “Over 150 years, the government used those children to take away that culture, and now you see children bringing back that culture and doing it in such a strong way. I admire it, and I’m so proud to see where they’re at.”

Horton hopes people understand the fact that this affected hundreds of thousands of Native Americans, and the “generational trauma” communities still face today.

Hall pointed out how “collective” the experience was, mentioning researchers, tribal councils, elders and the many different perspectives incorporated into the documentary. “To have this history researched and then returned to the tribe is humongous,” Hall said. “So that way the next person that comes along, at least they have a starting point. It was a gift to all of us.”

She also described how “healing” it was to know their history will be on OPB and PBS and in-person. “It says you are important,” she said, “we acknowledge that this happened and this is important history.”

The journey to create this documentary was “extremely heavy” for Hall. She cried her way through the devastating information she uncovered. She started hyperventilating when she found out about a story of a 12-year-old Klamath tribal member named Charlie Fiester who was shot running from Chemawa Indian School.

Her cousin’s words put her at peace: “These boarding schools, it’s like an unbroken bone. For 100 years, we’ve just patched it up to make it through the day. Now it’s time to break that bone and set it and let it heal properly.”

While this project “opened some wounds,” it was also “part of setting that bone so we can properly heal.” Her voice broke and she wiped her tears with a tissue.

She hopes the documentary will give the audience a better understanding of why Indigenous people may view schools, hospitals, federal governments and other institutions with a “learned lens” of distrust.

“If you truly understand the history,” Hall said, “it creates empathy.”

Hall reminded viewers to realize the strength and have appreciation for the present era. She said, “It is truly educational. It could sit heavy on the heart, and it takes a while to process.”

This story originally appeared in Ashland.news and was republished here with permission.